Target

Our target in this lesson will be Wesnoth 1.14.9.

Identify

In the previous lesson, we identified the packets used for connecting to a Wesnoth server. We then wrote a client that would replay these packets. In this lesson, we will identify the packets used for sending chat messages and reverse their structure. This will allow us to create our own legitimate packets instead of only replaying packets.

Understand

For clients and servers to communicate over a network, both sides must agree on how to structure the data in each packet. Since this structure must be reversible for each side, we can also reverse it. Once the data is reversed, we can modify the data and do the opposite of the reversing process to create a new packet.

Chat Packets

Similar to reversing an executable, it is helpful to have a context when reversing packets. With executables, this context is often a string that we have observed inside the executable. When it comes to packets, this context is some type of data we can control in the packet.

Typically, you control several pieces of data in a packet. For example, most games allow you to set your name. Other games will allow you to connect with multiple versions or certain mods. Both of these pieces would allow you to associate certain data with certain packets. However, one of the easiest pieces of data to control is a game’s chat messages. Since Wesnoth allows players to send chat messages, this is the context we will use for this lesson.

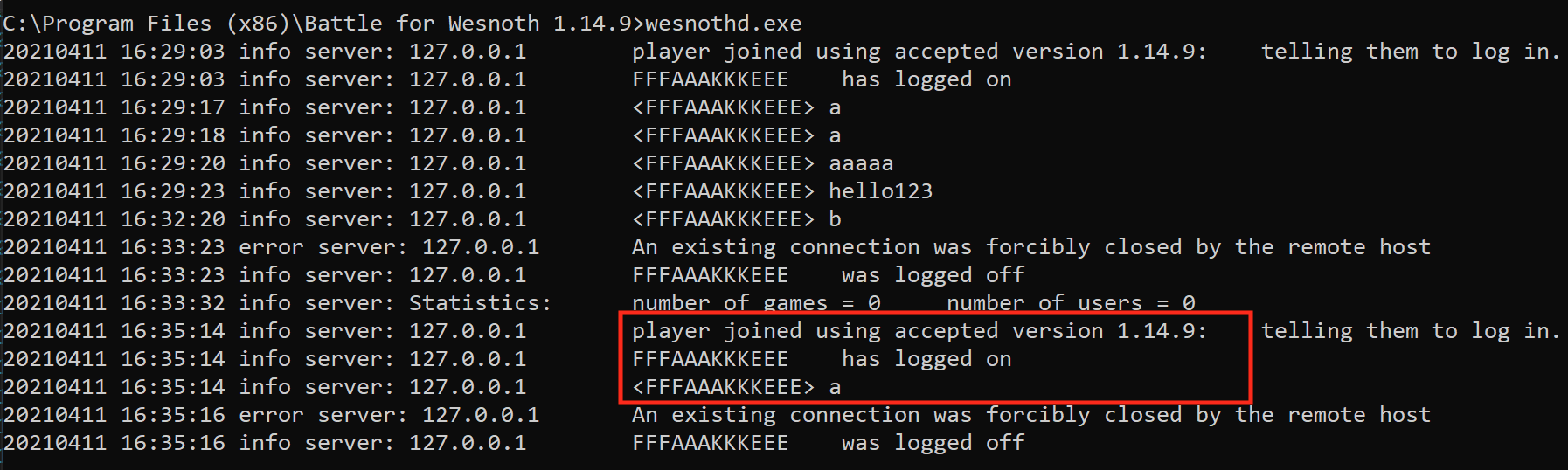

Start Wesnoth and connect to your local server with a user named FFFAAAKKKEEE, identically to the last lesson. Once connected, start Wireshark to log packets. To help reverse the game’s packets, we want to answer a few questions:

- Is there any randomness or time element encoded in the packets?

- Can we observe patterns of letters in the packets?

- Can we observe any human-readable characters in the packets?

To answer these questions, we can send the following four chat messages:

- a

- a

- aaaaa

- hello123

The first two messages are identical and will help us determine if identical messages result in identical packets. The third message repeats a several times, allowing us to observe any type of data patterns. Finally, the last message will immediately tell us if it appears readable in a packet.

Test Cases

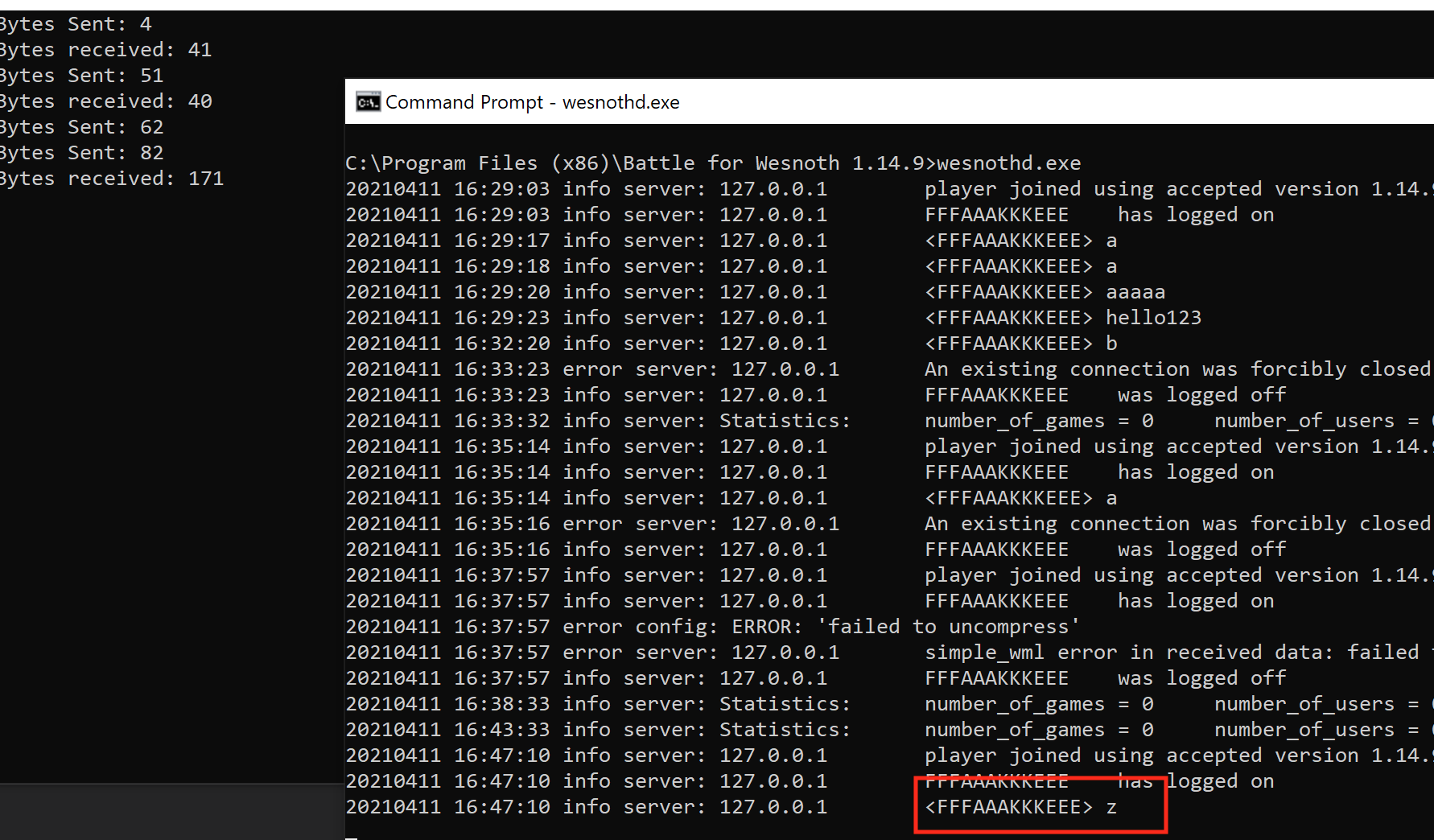

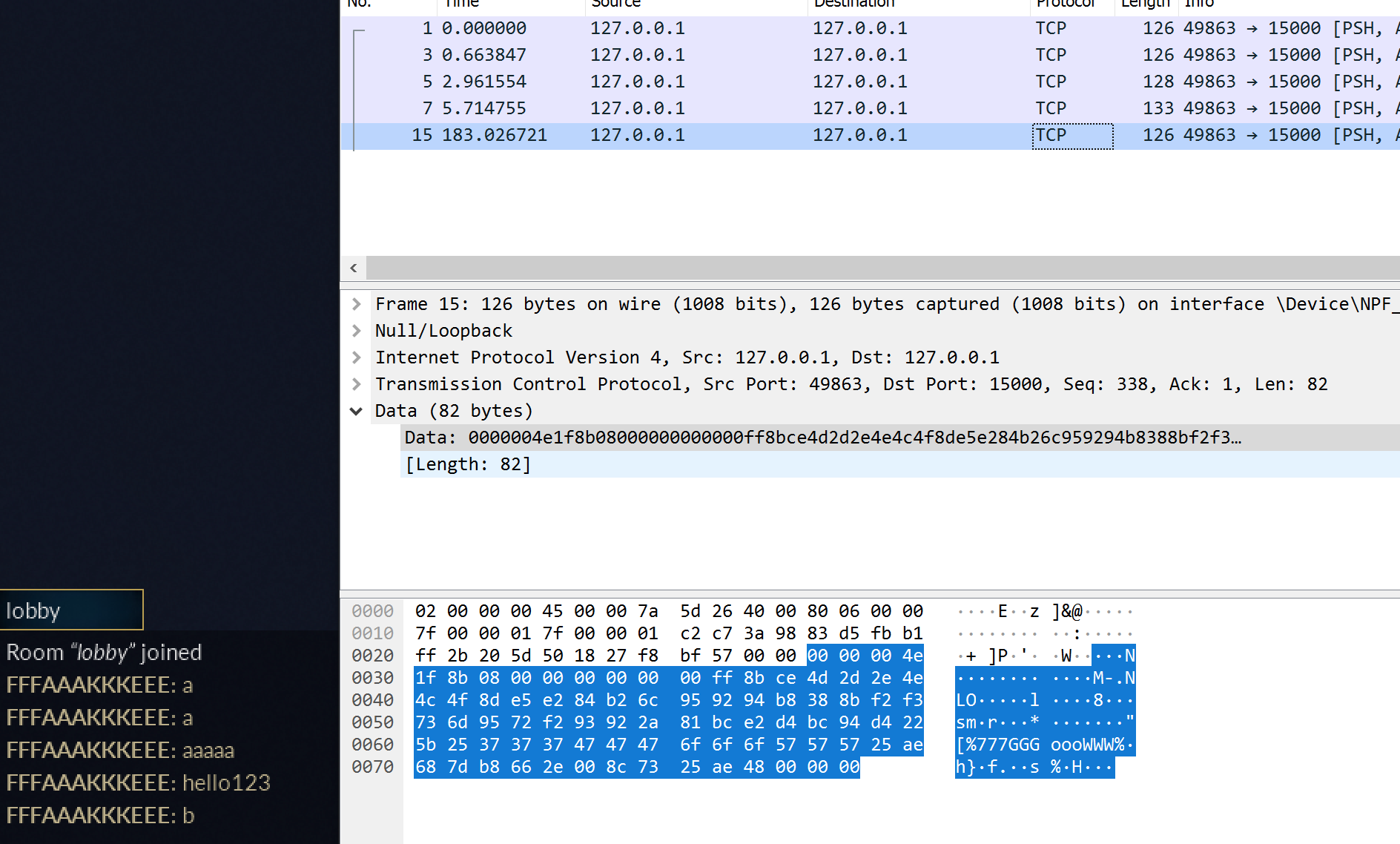

Examining the data of the first two packets (a and a), we can see that their data is identical. This means that the packets do not contain a timestamp or any other uniqueness factor:

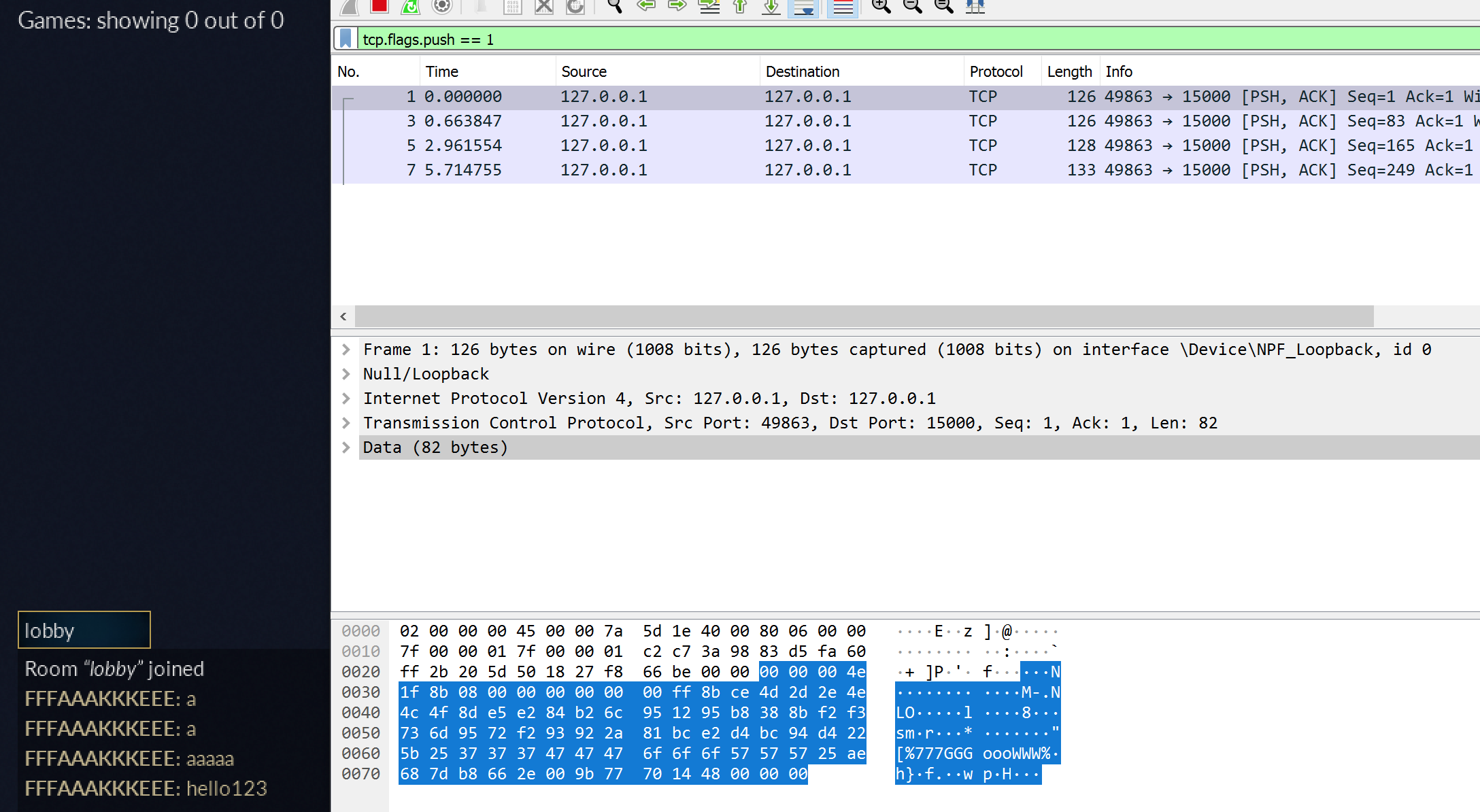

Next, examining the data of the third packet (aaaaa), we see a pattern toward the end:

This pattern is too long for aaaaa, and its structure of 3-3-3-3 is closest to our player’s name (FFFAAAKKKEEE). We can see that this pattern also occurs in all of our messages, indicating that one element of this packet must contain our player’s name.

Finally, examining the data of the last packet, we cannot observe anything that would resemble hello123.

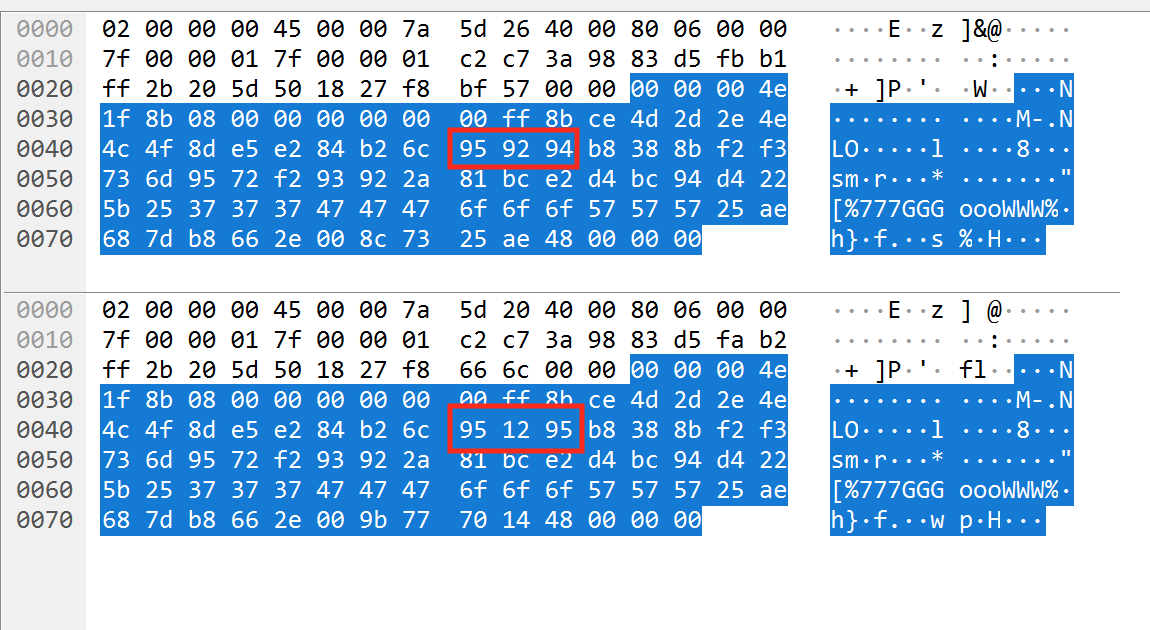

Next, let’s observe the difference between the packets for the message a and a new message b to help determine how single characters are handled:

Comparing these two packets side by side, we find that the single-character modification resulted in 2 of the bytes being changed in the middle of the packet, and several bytes being changed at the end:

This demonstrates that our text is not being mapped one-to-one into a packet, and additional processing is taking place. With this information, we can close Wesnoth and stop logging packets in Wireshark. However, make sure to keep Wireshark running so we can grab packet data as we analyze it further.

Packet Modification

Now, let’s see how the server responds if we modify a packet. In the last lab, we wrote a client that would connect to the server with the username FFFAAAKKKEEE. We can expand on this code to send a chat message a after we connect.

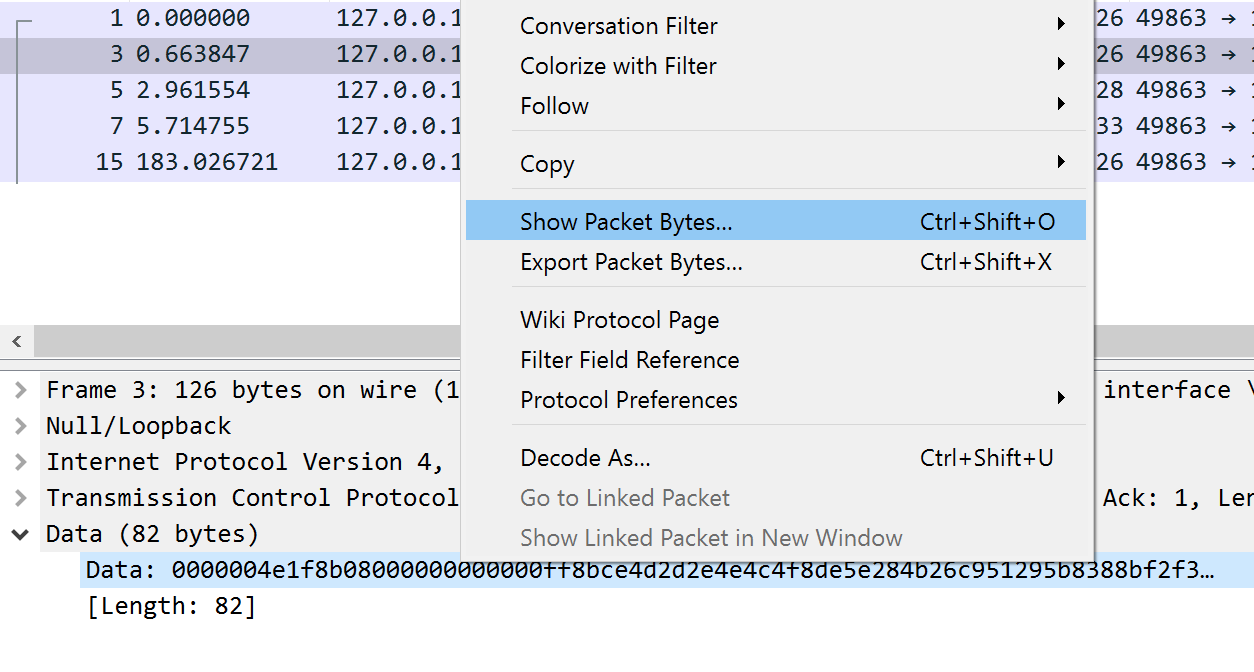

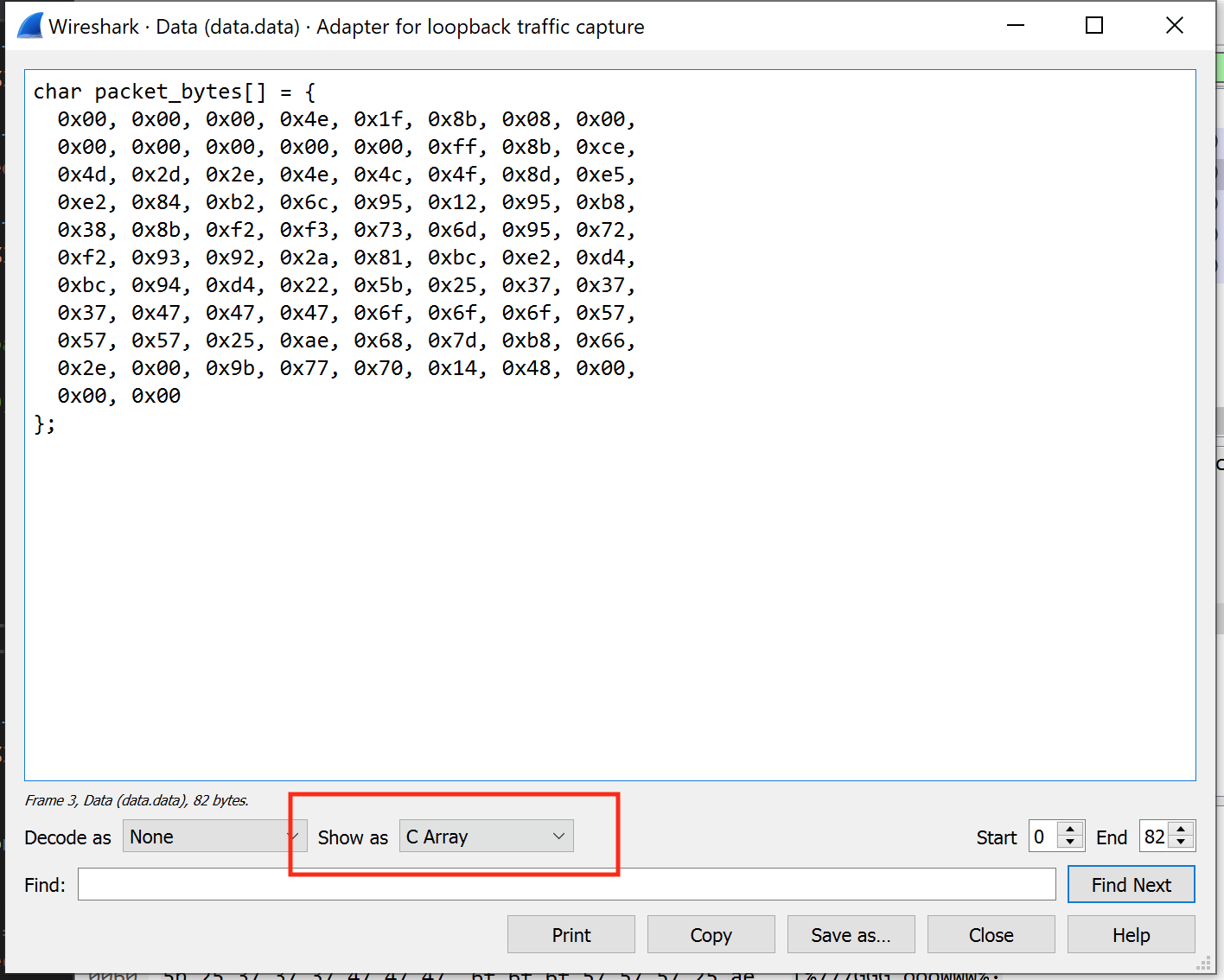

In Wireshark, click on the first or second packet (the a messages) and select the data. Right-click and choose Show Packet Bytes:

In the window that appears, choose C Array in the Show As section. This will format the packet’s data into an array that can be dropped directly into your code.

After we have sent the handshake, version, and username packets, we can add the following code to send the chat message:

const unsigned char packet_bytes[] = {

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x4e, 0x1f, 0x8b, 0x08, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xff, 0x8b, 0xce,

0x4d, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x4e, 0x4c, 0x4f, 0x8d, 0xe5,

0xe2, 0x84, 0xb2, 0x6c, 0x95, 0x12, 0x95, 0xb8,

0x38, 0x8b, 0xf2, 0xf3, 0x73, 0x6d, 0x95, 0x72,

0xf2, 0x93, 0x92, 0x2a, 0x81, 0xbc, 0xe2, 0xd4,

0xbc, 0x94, 0xd4, 0x22, 0x5b, 0x25, 0x37, 0x37,

0x37, 0x47, 0x47, 0x47, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x57,

0x57, 0x57, 0x25, 0xae, 0x68, 0x7d, 0xb8, 0x66,

0x2e, 0x00, 0x9b, 0x77, 0x70, 0x14, 0x48, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00

};

iResult = send(ConnectSocket, (const char*)packet_bytes, (int)sizeof(packet_bytes), 0);

printf("Bytes Sent: %ld\n", iResult);

Executing this code will send a chat message just as if we were connected:

In the section above, we saw that the difference between the a and b chat messages was a change of 2 bytes. Let’s change only the 2 bytes above and see how the server responds:

const unsigned char packet_bytes[] = {

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x4e, 0x1f, 0x8b, 0x08, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xff, 0x8b, 0xce,

0x4d, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x4e, 0x4c, 0x4f, 0x8d, 0xe5,

0xe2, 0x84, 0xb2, 0x6c, 0x95, 0x92, 0x94, 0xb8,

0x38, 0x8b, 0xf2, 0xf3, 0x73, 0x6d, 0x95, 0x72,

0xf2, 0x93, 0x92, 0x2a, 0x81, 0xbc, 0xe2, 0xd4,

0xbc, 0x94, 0xd4, 0x22, 0x5b, 0x25, 0x37, 0x37,

0x37, 0x47, 0x47, 0x47, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x57,

0x57, 0x57, 0x25, 0xae, 0x68, 0x7d, 0xb8, 0x66,

0x2e, 0x00, 0x9b, 0x77, 0x70, 0x14, 0x48, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00

};

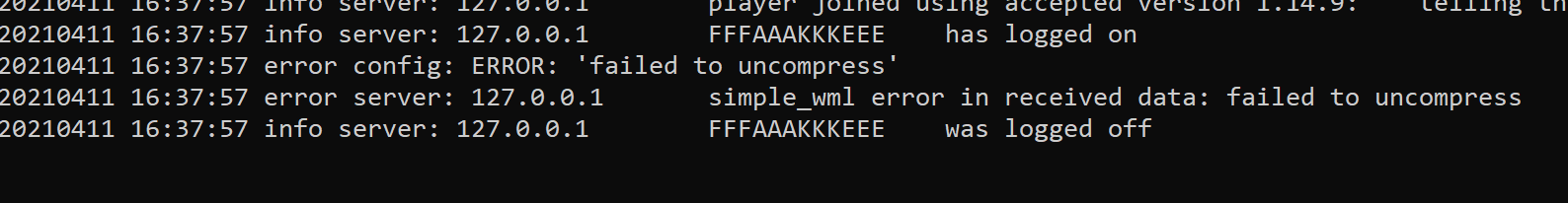

Executing the code with this packet will result in the following error from the server:

This error message, plus how a single letter change results in multiple modifications to the bytes in the packet, indicates that at least some part of the packet is compressed.

Compression

Compression is the process of taking input data and reducing its size. One of the most simplistic compression techniques is combining repeating data. For example, the string AAAAAAAAAA could become 10A. When decompressed, the decompressor would know to expand 10A back to AAAAAAAAAA. There are multiple ways to compress data, with some popular formats being ZIP and RAR. Just like executables are always distinct from other data (like pictures), different compression formats are distinct from each other.

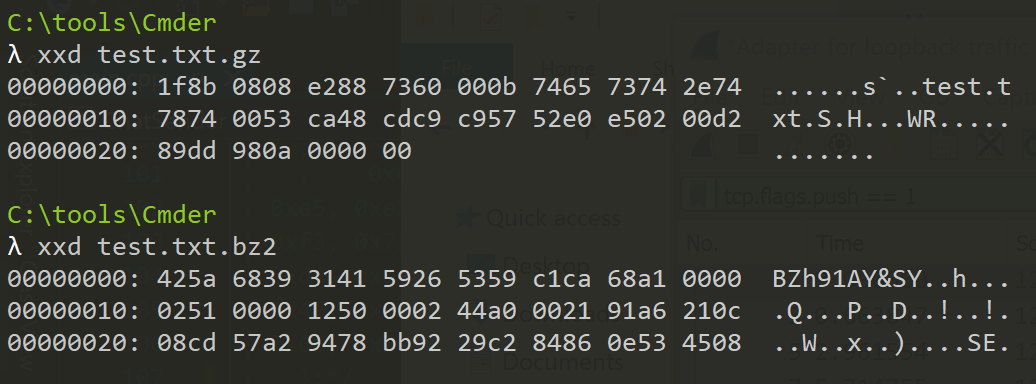

Wesnoth is a multi-platform game that supports Windows and Linux. Therefore, we know that whatever format being used must run on both OS’s. On Linux-based systems, two of the most popular compression formats are gzip and bzip2. We will start our investigation with these formats.

Windows’ default command prompt does not have good support for data operations. To help us investigate, we will use another terminal emulator called Cmder. We will also install the gzip package. Both of these can be installed using Chocolatey in Powershell:

choco install cmder -y

choco install gzip -y

To test out the two compression techniques, create a text file named test.txt. In this file, add a single line of text. Next, open up Cmder (C:\Tools\Cmder.exe) and navigate to the directory with this text file. Run the following command to create a gzip’d version of the file:

gzip test.txt

By default, gzip will remove the original file. Recreate test.txt in the same way so that you can then create a bzip’d version:

bzip2 test.txt

You should now have two files: test.txt.gz and test.txt.bz2. We next want to examine what the bytes of these files look like. To do this, we can use a tool called xxd:

xxd test.txt.gz

xxd test.txt.bz2

Your results should look similar to the following:

Comparing these against one of the packets, you should immediately notice

that the beginning bytes (0x1f8b) jump out in the packet:

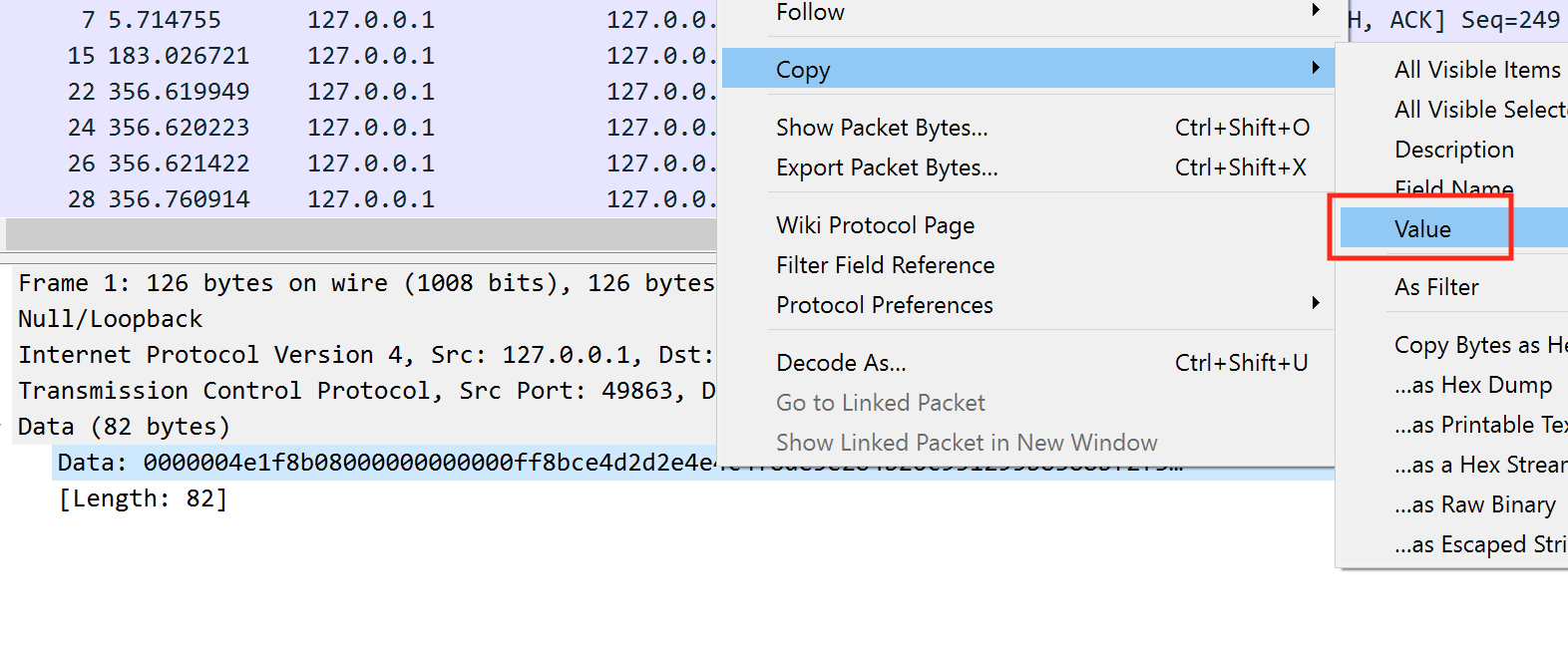

This indicates that part of the packet may be compressed with gzip. We can validate this by attempting to decompress an actual packet. In Wireshark, select a packet, right-click on the data, and choose Copy -> Value:

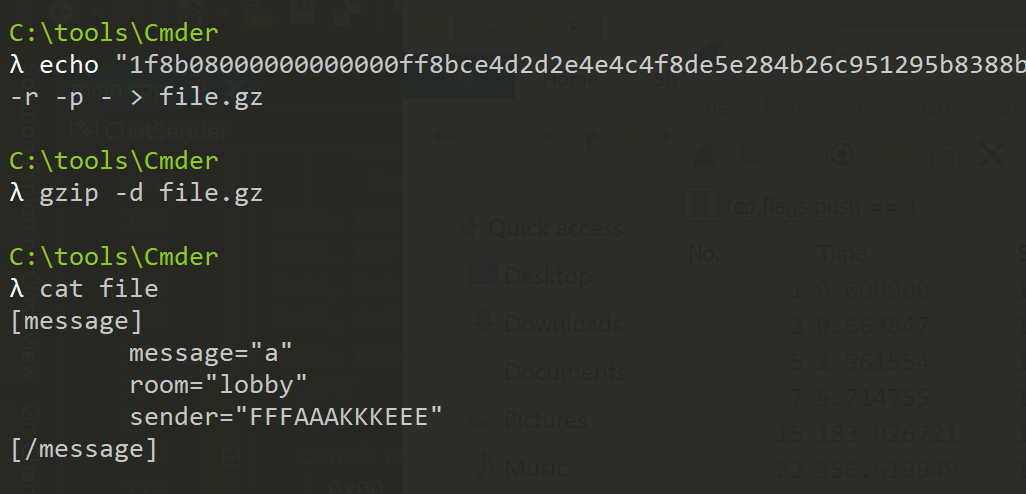

We can use xxd again to turn this data into a gzip’d file. To do this, we will first print the data to the terminal using the command echo. However, instead of only printing, we will pass this printed text to xxd via the pipe operator (|). We can then use the -r switch to tell xxd to reverse the operation (or create a file from the hex), and the -p switch to tell xxd to read from whatever is typed in, in this case the echo command. Finally, we use the redirection operator (>) to save this to a compressed file:

echo "1f8b08....." | xxd -r -p - > file.gz

We can then decompress this file using gzip:

gzip -d file.gz

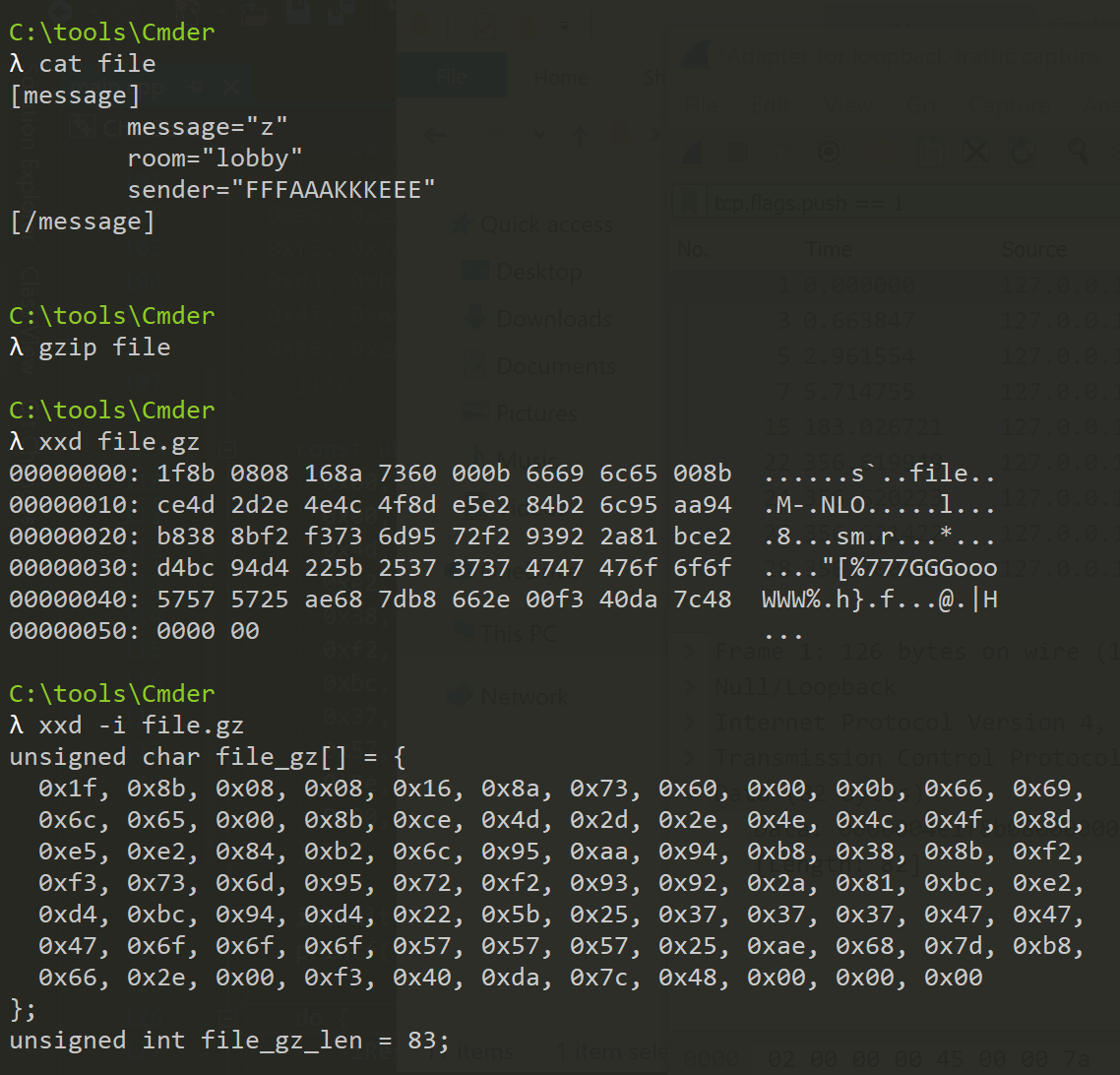

This will produce a text file named file. Viewing this file, we can see structured data representing our chat message:

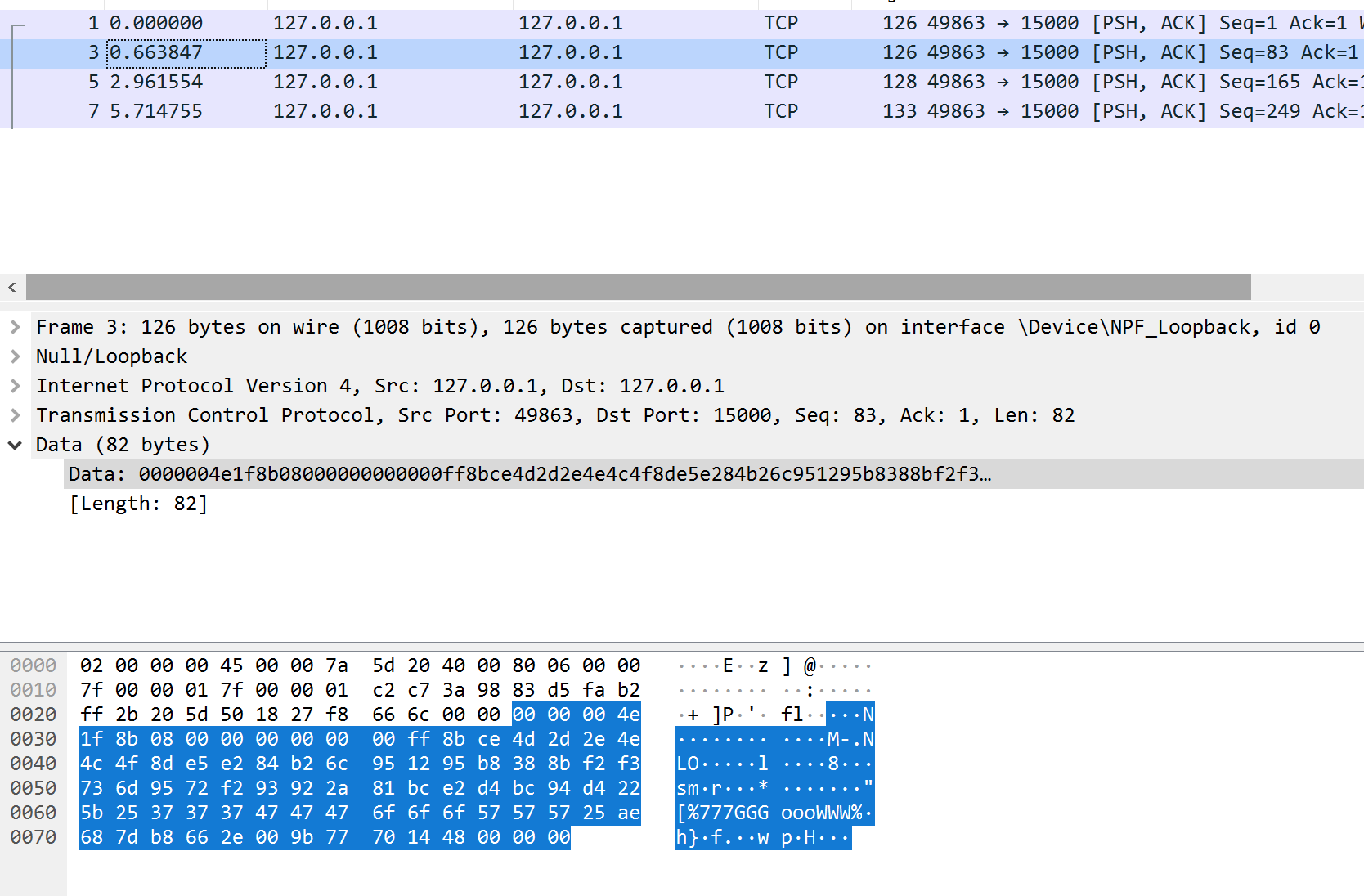

Packet Structure

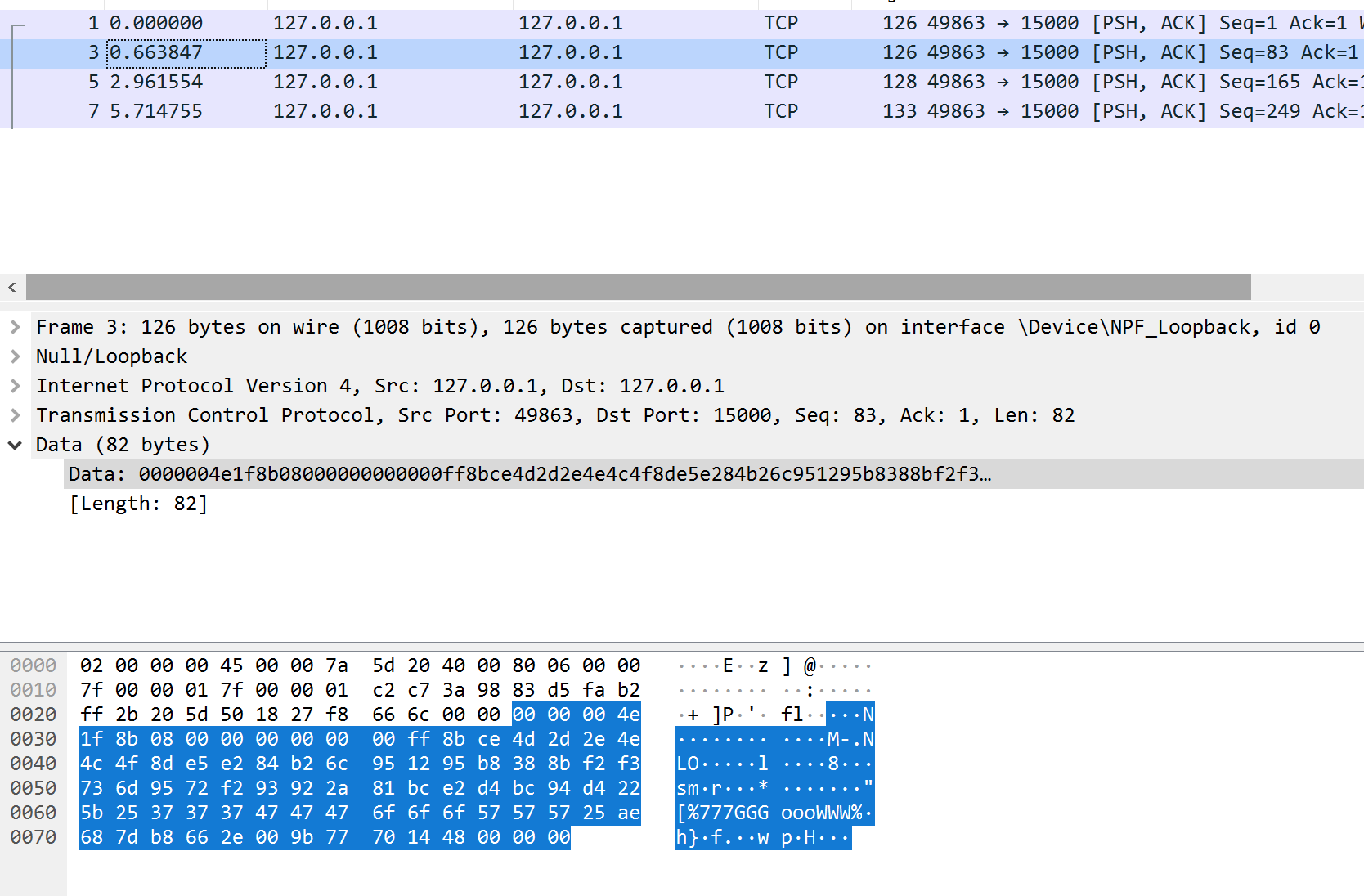

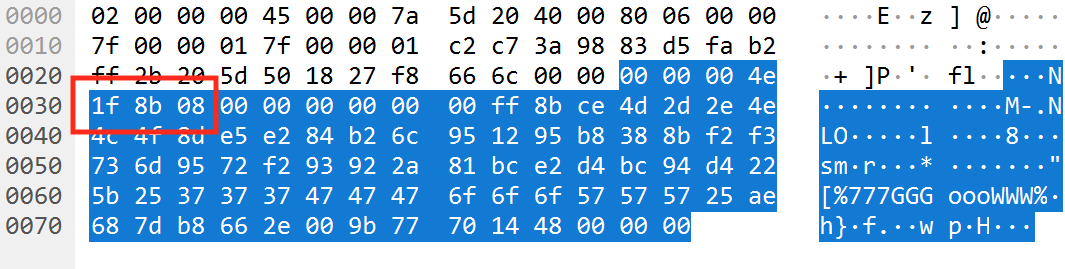

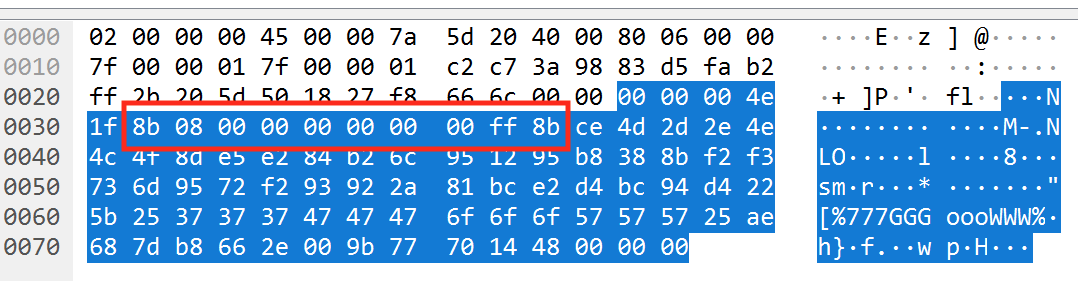

We now know that the majority of the packet contains compressed data, but

there is still one piece of the packet we have not reversed yet. Looking

at the packet again, we can see that the data

0x00 00 00 4e comes before the compressed section:

If we convert this 0x4E into decimal, we get the value 78.

Examining the length of the data section of the packet, we see that it is 82. From this we can deduce that the first 4 bytes of the packet are

responsible for holding the size of the compressed data. With this, we

have all the information we need to create our own packet.

Creating a Packet

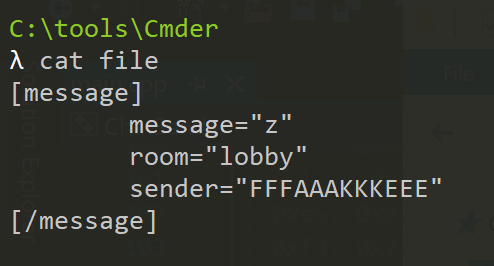

Now that we have reversed a packet, we can use the opposite steps to create our own. In this case, let’s create a chat message that says z from our chat message that said a. Take the file produced from our steps above, and change the message to z:

Next, we are going to gzip this file. We can then use xxd to print out its byte representation. By using the -i flag, xxd will display this data in a format that we can use in our code:

We can place this data into our code like before:

const unsigned char packet_bytes[] = {

0x1f, 0x8b, 0x08, 0x08, 0x16, 0x8a, 0x73, 0x60, 0x00, 0x0b, 0x66, 0x69,

0x6c, 0x65, 0x00, 0x8b, 0xce, 0x4d, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x4e, 0x4c, 0x4f, 0x8d,

0xe5, 0xe2, 0x84, 0xb2, 0x6c, 0x95, 0xaa, 0x94, 0xb8, 0x38, 0x8b, 0xf2,

0xf3, 0x73, 0x6d, 0x95, 0x72, 0xf2, 0x93, 0x92, 0x2a, 0x81, 0xbc, 0xe2,

0xd4, 0xbc, 0x94, 0xd4, 0x22, 0x5b, 0x25, 0x37, 0x37, 0x37, 0x47, 0x47,

0x47, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x57, 0x57, 0x57, 0x25, 0xae, 0x68, 0x7d, 0xb8,

0x66, 0x2e, 0x00, 0xf3, 0x40, 0xda, 0x7c, 0x48, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

};

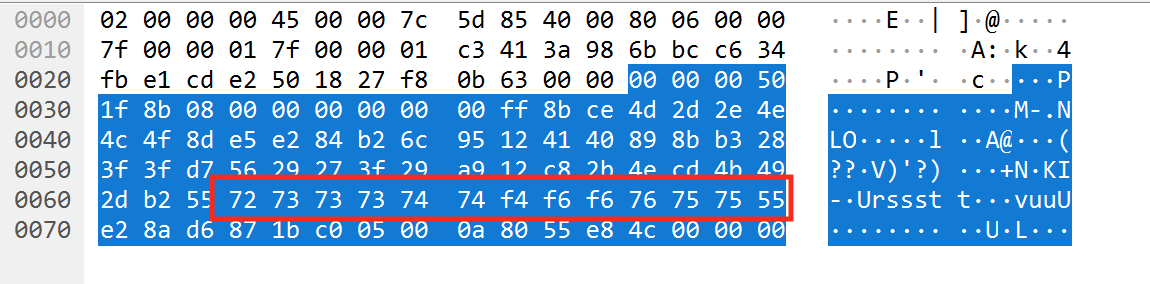

If you examine the chat messages so far and our newly generated message, you may notice that there is a difference:

All the other chat messages used by the game have 0x00…ff in

between 0x08 and 0x8b. By contrast, our message

has what appears to be random data. To fix this, we can simply replace

these bytes with values that we know work from the game:

const unsigned char packet_bytes[] = {

0x1f, 0x8b, 0x08, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xff, 0x8b, 0xce,

0x4d, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x4e, 0x4c, 0x4f, 0x8d, 0xe5, 0xe2, 0x84, 0xb2, 0x6c,

0x95, 0xaa, 0x94, 0xb8, 0x38, 0x8b, 0xf2, 0xf3, 0x73, 0x6d, 0x95, 0x72,

0xf2, 0x93, 0x92, 0x2a, 0x81, 0xbc, 0xe2, 0xd4, 0xbc, 0x94, 0xd4, 0x22,

0x5b, 0x25, 0x37, 0x37, 0x37, 0x47, 0x47, 0x47, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x57,

0x57, 0x57, 0x25, 0xae, 0x68, 0x7d, 0xb8, 0x66, 0x2e, 0x00, 0xf3, 0x40,

0xda, 0x7c, 0x48, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

};

This also has the effect of shortening the data. Finally, we need to add

the length to the front of the packet. Since it is a single letter, we

know that it will be 0x4e:

const unsigned char packet_bytes[] = {

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x4e, 0x1f, 0x8b, 0x08, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0xff, 0x8b, 0xce, 0x4d, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x4e, 0x4c, 0x4f, 0x8d, 0xe5,

0xe2, 0x84, 0xb2, 0x6c, 0x95, 0xaa, 0x94, 0xb8, 0x38, 0x8b, 0xf2, 0xf3,

0x73, 0x6d, 0x95, 0x72, 0xf2, 0x93, 0x92, 0x2a, 0x81, 0xbc, 0xe2, 0xd4,

0xbc, 0x94, 0xd4, 0x22, 0x5b, 0x25, 0x37, 0x37, 0x37, 0x47, 0x47, 0x47,

0x6f, 0x6f, 0x6f, 0x57, 0x57, 0x57, 0x25, 0xae, 0x68, 0x7d, 0xb8, 0x66,

0x2e, 0x00, 0xf3, 0x40, 0xda, 0x7c, 0x48, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

};

With these changes, we can build and execute the code. The resulting program will connect to the server and send the chat message z, proving that we now know the structure and can create our own packets: