Peer-2-Peer

Imagine that two neighbors want to play a game of chess. One approach may be to have Neighbor A set up a chess board in his house and give Neighbor B the house keys. At any point during the day, Neighbor A could make a move. However, if Neighbor B wants to make a move, he has to walk over to Neighbor A’s house. Additionally, if Neighbor B wanted to think on his move, he would need to take a picture or somehow record the copy of the chess board before he went back over to his own house.

This is an example of a Peer-2-Peer (P2P) model. In a P2P model, one player acts as the host and all other players act as guests. This is the model many console games use to handle multiplayer functionality. Its major downside is that the host will have an advantage in terms of response time. This is because all other players must connect to the host to retrieve and send updates, while the host can update his local copy.

Client-Server

Imagine now that Neighbor A and B want to play chess, while another neighbor (C) wants to observe the chess game. This time, each neighbor has their own chess board and all players agree that an additional neighbor (D) will be the judge. The judge is the most trusted party of all involved and his roles are making sure no illegal moves happen and maintaining the “correct” version of the chess board.

To make a move, Neighbor A would write his move on an envelope and place the envelope in Neighbor D’s mailbox. Neighbor D would then ensure that the move is legal, update his board, and then place letters in Neighbor B and C’s mailboxes containing the move. Neighbors A, B, and C are all responsible for updating their boards to match the board of Neighbor D. If Neighbor A delivers a move that is impossible, Neighbor D will warn him that it appears his board is not up-to-date and he cannot make that move.

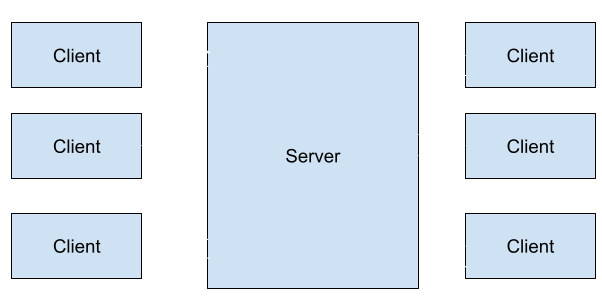

This is an example of a client-server model, which we briefly discussed in the Game Fundamentals lesson.

In a client-server model, the server is a trusted entity that all clients connect to. When playing a multiplayer game, the server will not directly participate in the game, but it is responsible for keeping a trusted copy of the game’s state. Each client will send updates to the server, and the server will distribute those updates to other clients. If a player sends too many updates that are not legal, the server will warn the client that it is desynchronized before kicking the client off.

Packets

In the client-server chess example, each neighbor placed an envelope with their move inside Neighbor D’s mailbox. In networking, these envelopes are known as packets. Just like envelopes, packets contain who the packet is from, who the packet is going to, and the data itself. For example, if a player sends a chat message of hello in a multiplayer game like Wesnoth, the packet might contain the following information:

source: player

destination: server

data: hello

The larger the packet, the more time it will take to transmit from the client to the server. The more time it takes, the more lag is present in the client and server communication. To ensure that lag is at a minimum, packets contain the minimum amount of information possible. For example, if a client wants to say they fired a single shot from their weapon, the packet might look like:

source: player

destination: server

data: f1

In this example, both the client and server agree that f means fire and 1 means 1 round.

Network Protocols

If you want to tell someone, “I like this restaurant,” you need to ensure that you are speaking the same language as the other person. Depending on their language, the syntax or structure of this sentence may differ, or certain words may be conjugated differently. This same logic applies when sending packets over a network. These communication rules are called protocols. These protocols determine how both the source and destination will communicate and how individual packets will look. The two main protocols you will encounter when looking at game network traffic are UDP and TCP.

Imagine you want to send a letter to the neighbor across the street, reminding him to water his plants. You do not expect a response to this letter, so you give it to your dog to take over to him. You would like this letter to get to him, but you will not be particularly upset if it does not. This is an example of UDP, in which packets are sent without any method to determine that they have arrived.

Now imagine you want to exchange multiple letters with your neighbor. Since you will be responding directly to what your neighbor says, you want to ensure that all letters are delivered. You and your neighbor agree to light your respective porch lights when you have received a letter. This is an example of TCP, in which an upfront connection is established and packets are acknowledged as delivered.

The data contained within TCP and UDP packets can be identical, but the packets will be different. This is because each protocol has a different header that is used by both the source and the destination to understand the data in the packet.

Sockets

Both TCP and UDP packets use the Internet Protocol (IP) to handle the process of routing the packet from the source to the destination. Each network device has an IP address that represents that device’s “location”. To differentiate between types of traffic (such as web browsing, email, or video chat), packets also have a port number. For example, to browse a website over HTTP, you could visit 123.45.67.89 on port 80. While browsing, you could also connect to this machine using SSH, another service, on port 22. Both of these requests could be handled simultaneously as they are being handled by different programs listening on different ports.

An IP:Port pair is sometimes referred to as a socket. Sockets represent endpoints that can be communicated with. Windows has an API known as WinSock to enable programmers to quickly write programs that communicate to different destinations over TCP or UDP.