Target

Our target in this lesson will be Wesnoth 1.14.9.

Identify

In this lesson, we will print our own text in Wesnoth. To accomplish this task, we will first locate a section of code responsible for printing text. Then, we will use a code cave to modify the game’s memory to display our text.

Understand

There are multiple approaches to print our own text inside a game:

- Use an external overlay.

- Create a code cave inside the game’s main display loop and call the function responsible for displaying text.

- Create a code cave inside a function responsible for displaying text and modify the text about to be displayed.

Different games are suited best for different methods. For this lesson, we will use the third approach as it is the easiest to do in Wesnoth. We will examine the other approaches more in-depth in future lessons.

Locating Text

Our first task is to locate the game’s code that is responsible for displaying text. To start, we need to find a string of letters that appears in the game. For Wesnoth, we can use the Terrain Description text that is displayed when clicking on a tile. Any description will work, but for this lesson, we will use the description for the Ford tile. For other games, chat messages are a good starting location.

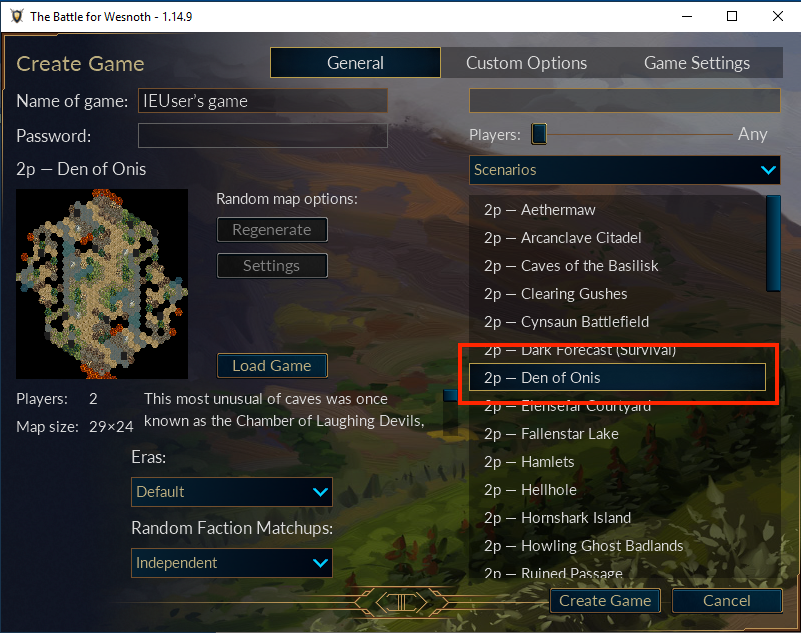

First, select a map that has Ford tiles on it. Den of Onis is one example:

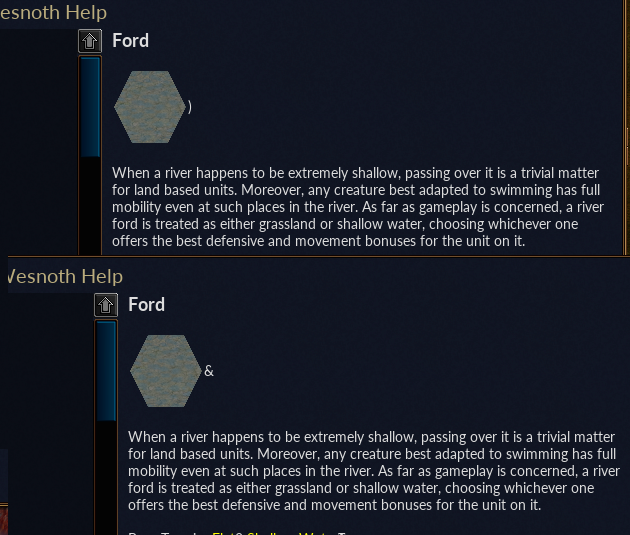

When the map loads, select a Ford tile and select the Terrain Description entry on the context menu:

This will bring up the description for the tile, which contains a long string of text:

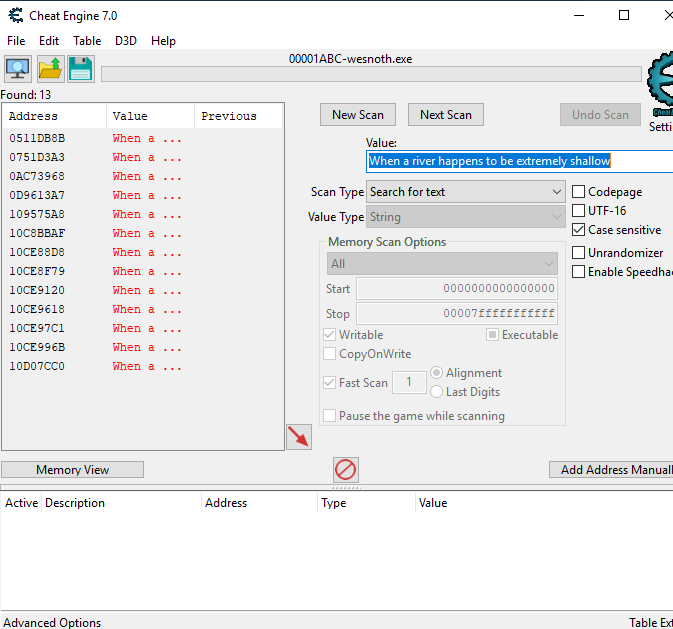

We can use Cheat Engine to search for where this text is stored within the game. Make sure to close down the terrain description box before searching to reduce the amount of results. Due to the unique nature of the text, we only need to search for a couple words:

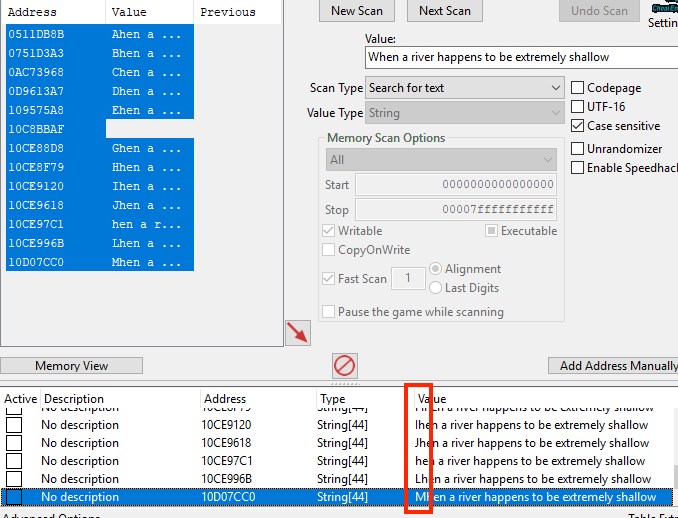

To narrow down which address represents the string we are interested in,

change the first letter of every string. After changing these values, go

back into Wesnoth and examine the terrain description again. The version

of the string that is displayed in game will match up with the correct

address. In this case, the string starting with Lhen was displayed,

making our address 0x10CE996B.

Locating PrintText

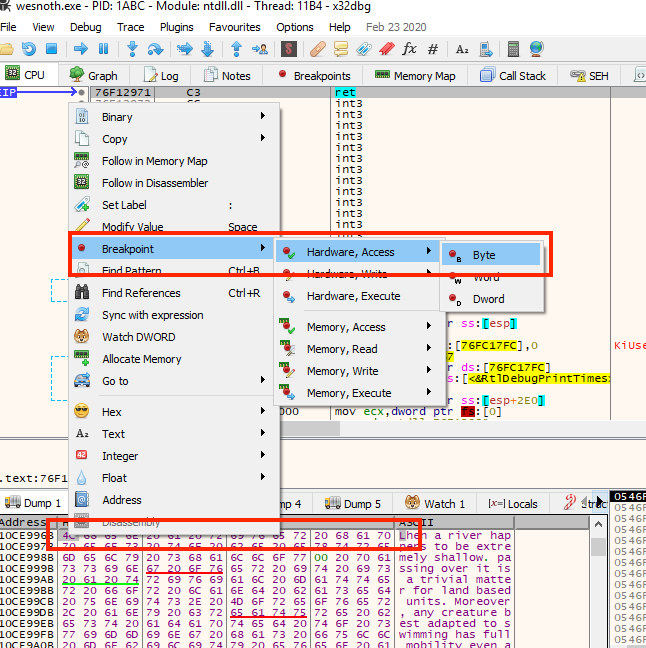

We can now use the address we found to locate the function responsible for printing text. We know that the print text function must access this text in some way to print it. To determine where this function is, we can set a breakpoint on a byte of the text.

With the breakpoint set, go back into Wesnoth and invoke the Terrain Description action again. Your breakpoint will pop immediately:

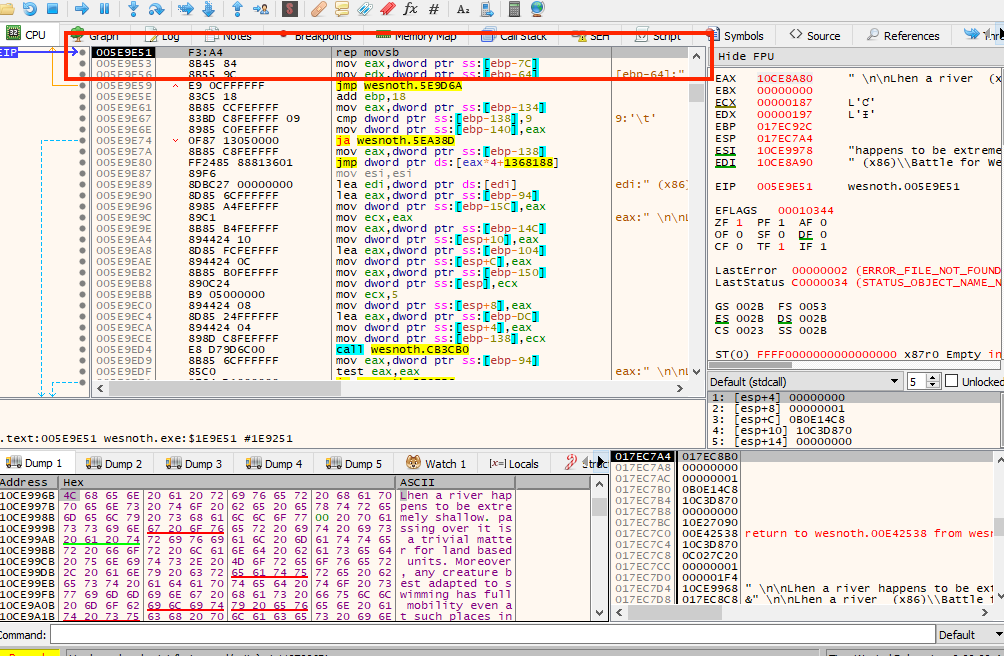

Examining this code, we appear to be in a loop responsible for moving each byte of the text into a buffer. Like we did in previous lessons, we want to navigate to the code that called this lower-level code by using execute until return and stepping out.

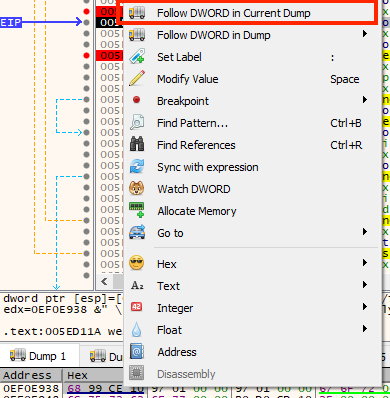

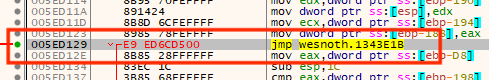

This call looks like it could be responsible for populating the terrain

description box with text. If we continue execution, we notice that this

code is called multiple times for each section of the terrain description

box. To determine the parameters passed to this call, we can set a

breakpoint on 0x005ED114 and invoke the

Terrain Description action again:

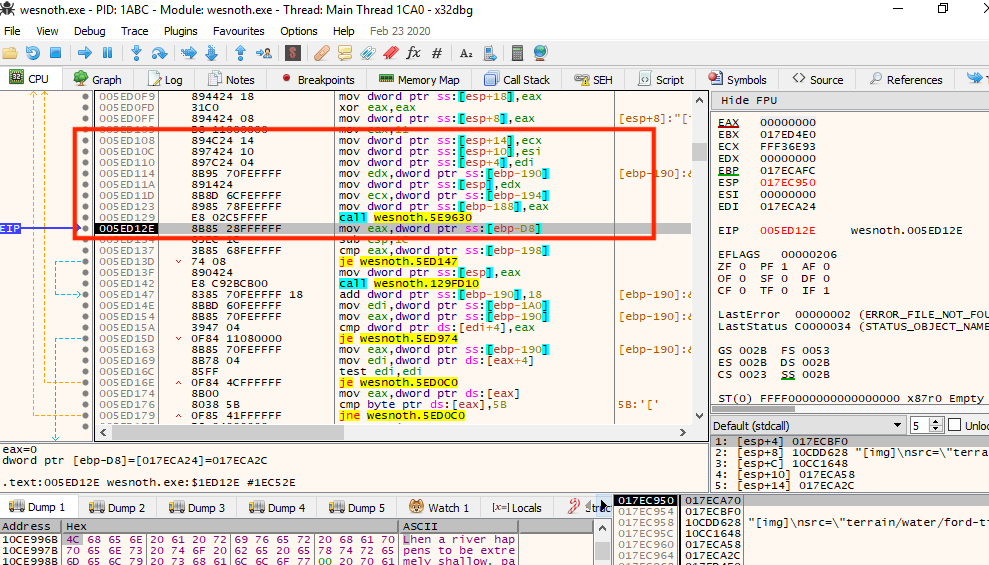

The highlighted section shows that the text is loaded into the register

edx. The code at 0x005ED11A then moves the

value in edx into the location pointed at by

esp. This is identical to pushing the value of

edx on the top of the stack. While we have not discussed

the stack yet, for the purpose of this lesson, we need to know that functions

will often retrieve values off of the stack for use in execution.

Memory and Endianness

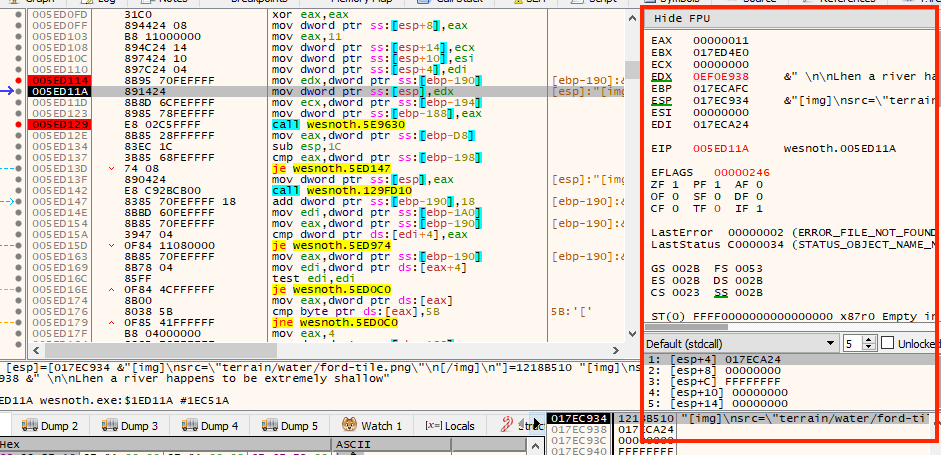

You may have noticed that the address in edx does not match the address we found in Cheat Engine. Since the text space is dynamically allocated, we will need to understand how to retrieve the value of the text from edx to create our code cave.

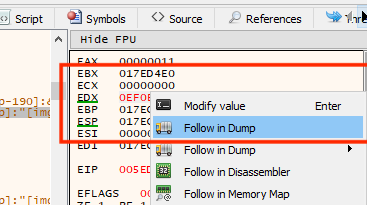

Invoke the Terrain Description action again to force our breakpoint to pop. Once it does, right-click on the value of edx and choose Follow in Dump:

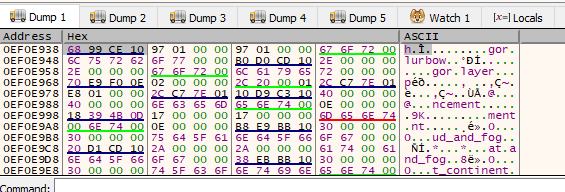

This will change the current address displaying in the dump to the value of edx. As we discussed in previous lessons, the dump section displays the current running memory of a process. It’s important to remember that both the dump section and Cheat Engine are displaying and searching the same data.

This value stored in edx is obviously not a text string. However, if we examine the value of the bytes, we see that they share many similarities to the address we found in Cheat Engine. In the previous lesson, we briefly discussed a concept known as endianness. Most Windows-based CPU’s are little endian. By definition, this means that the least-significant byte is stored in the smallest address.

In practice, this means that when the address 0x12345678 is

stored in memory, it will be stored as 0x78 56 34 12. In this

case, 0x78 represents the least-significant byte, or the

smallest value. A good comparison is to imagine the number 123. Expressed

in a longer form, this value can be understood as 1100 + 210 + 3*1. The

smallest value in this form is the number 3.

The second part of this definition can be understood by examining the dump. In the dump, memory addresses grow from a lower value to a higher value. Because of this, the least-significant byte will be stored “first” in memory. The combination of these factors make addresses stored in memory appear to be “reversed”.

Now that we understand endianness, we can conclude that the value stored at edx is an address. We can quickly navigate to this address in the dump by selecting all the bytes and selecting Follow in Dump again:

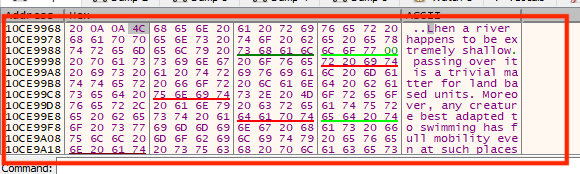

After selecting this, we arrive at our string’s location in memory:

To reference this value in assembly, we can make use of the ptr ds keyword:

mov eax, dword ptr ds:[edx]

This will load the value of the address stored in

edx into eax. In this case, it would

load the value 0x10CE9968 into eax. We could

then use the ptr ds keyword again to access the

individual bytes of the text.

Changing Text

With this reversing done, we can start creating our hack. To verify that we have the correct method, we will create a code cave that will change the text displayed each time the Terrain Description action is invoked. To do this simply, we will increase the value of the first byte each time our code cave is executed. This will change the value of the character and allow us to confirm that our hack is working.

Since we know the call at 0x005ED129 is

responsible for printing the text and is also 5 bytes long, we will use it

as our redirection point. As discussed in previous code cave lessons, any

location near the end of program’s memory will work for our cave location.

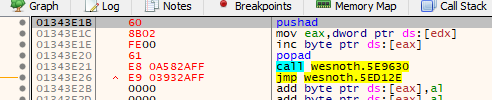

In this case, we will create it at 0x01343E1B. As usual, we

will replace the hooking location with a jump to our code cave:

We will first save the registers in our code cave. Then we will use the ptr ds keyword to load the value of the text from edx into eax. After that, we will use the inc operator to increase the value of the first byte of the string. For example, if the first byte is currently A (ASCII value 65), it will be increased to B (ASCII value 66). Finally, we will restore the registers, recreate the call, and then jump back to the original code.

With this completed, go back into Wesnoth and invoke the Terrain Description action multiple times. You will notice that a character after the image changes each time, demonstrating that we have successfully modified the text displayed.