Parts of a Game

While games are applications, they are complex and made up of several parts. Some of these include:

- Graphics

- Sounds

- Input

- Physics

- Game logic

Due to each part’s complexity, most games use external functions for these parts. These external functions are combined into what is called a library. Libraries are then used by other programs to reduce the amount of code written. For example, to draw images and shapes to a screen, most games use either the DirectX or OpenGL library.

For some types of hacks, it is important to identify the libraries being used. A wallhack is a type of hack that allows the hacker to see other players through solid walls. One method of programming a wallhack is modifying the game’s graphics library. Both OpenGL and DirectX are vulnerable to this type of hack, but each requires a different approach.

For most hacks, we will be modifying the game logic. This is the section of instructions responsible for how the game plays. For example, the game logic will control how high a character jumps or how much money the player receives. By changing this code, we can potentially jump as high as we want or gain an infinite amount of money.

Game Structure

Game logic is made up of instructions, like all computer code. Due to the complexity of games, they are often written in a high-level language and compiled. Understanding the general structure of the original code is often required for more complex hacks.

Most games have two major functions:

- Setup

- Main Loop

The setup function is executed when the game is first started. It is responsible for loading images, sounds, and other large files from the hard-drive and placing them in RAM. The main loop is a special type of function that runs forever until the player quits. It is responsible for handling input, playing sounds, and updating the screen, among other things. An example main loop might look like:

function main_loop() {

handle_input();

update_score();

play_sound_effects();

draw_screen();

}

All of these functions in turn call other functions. For example, the handle_input function might look like:

function handle_input() {

if( keydown == LEFT ) {

update_player_position(GO_LEFT);

}

else if( keydown == RIGHT ) {

update_player_position(GO_RIGHT);

}

}

Every game is programmed differently. Some games might prioritize updating graphics before handling input. However, all games have a main loop of some sort.

Data and Classes

Any data that can be updated in a game is stored in a variable. This includes things like a player’s score, position, or money. These variables are declared in the code. An example variable definition in C might look like:

int money = 0;

This code would declare the money variable as an integer. Like we learned in the last lesson, integer values in C are whole numbers (like 1, 2, or 3). Imagine if we had to track the money for several players. One way to do this would be to have several declarations, like so:

int money1 = 0;

int money2 = 0;

int money3 = 0;

int money4 = 0;

One downside to this approach is that it is hard to maintain as the game gets larger and more complex. For example, to write code that increases every player’s money by 1, we would have to manually update each variable:

function increase_money() {

money1 = money1 + 1;

money2 = money2 + 1;

...

}

If we added another player, we would have to go and update every section of code that altered the players’ money. A better approach is to declare these values in a list. We can then use an instruction known as a loop to go through every item in the list. This is known as iteration. In C, lists are commonly implemented using what is known as an array. For our purposes, you can assume lists and arrays are synonymous. One type of loop in C is known as a for loop. For loops are divided into three segments: the starting value, the ending value, and how to update the value after each iteration. An example of the previous code might be written like:

int money[10] = { 0 };

int current_players = 4;

function increase_money() {

for(int i = 0; i < current_players; i++) {

money[i] = money[i] + 1;

}

}

We now would only have to update the current_players variable to add support for another player.

To make it easier to develop complex applications, developers often use a programming model known as object oriented programming, or OOP. In OOP, variables and functions are grouped together into collections called classes. Classes are usually self-contained. For example, many games will have a Player class. This class will contain several variables like the player’s position, name, or money. These variables inside the class are known as members. Classes will also contain functions to modify these members. One example of a Player class might look like:

class Player {

int money;

string name;

function increase_money() {

money = money + 1;

}

}

Games will often contain lists of classes. For example, the game Quake 3 has an array of all the players currently connected to a server. Each player has their own Player class in the game. To calculate the score screen, the game will go over every player in the list and look at the amount of kills they have.

Memory

Games have a lot of large resources, like images and sounds. These must be loaded from the hard-drive, usually in the game’s setup phase. Once loaded, they are placed in RAM, along with the game’s code and data. Because games are so large, they must constantly load different data from the RAM into registers to operate on. This loading is typically done by a mov command. This command will move a section of memory into a register. Our increase_money example function executed by the CPU might look like:

function increase_money:

mov eax, 0x12345678

add eax, 1

mov 0x12345678, eax

In this example, we use 0x12345678 as the location in RAM of the player’s money. Most games will have this structure but a different location. For more complex games, these locations will be based on other locations. If our game had a Player class, the increase_money code executed by the CPU would need to use the Player’s class location to retrieve the money.

function increase_money:

mov ebx, 0x12345670

mov eax, ebx + 8

add eax, 1

mov ebx+8, eax

In this case, the CPU had to offset the money’s location based on the location of the Player class.

Multiplayer Clients

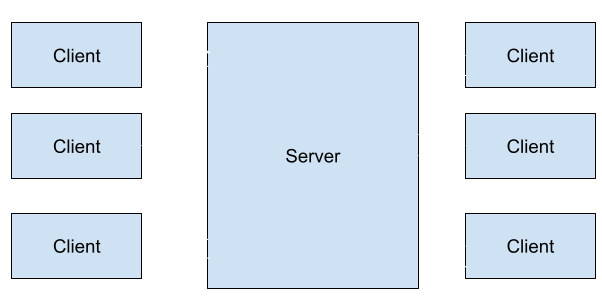

Multiplayer games allow multiple players to interact with each other. To allow this, multiplayer games make use of clients and servers. An example of the client-server model is shown below:

Clients represent each player’s copy of the game and contain all the information regarding the local game. For example, each client will contain that player’s money. When a player causes an action to change their money, the client is responsible for sending this update to the server.

Information can also be sent in both directions. An example of this is player movement. One client will tell the server that the player has moved their position. The server will then tell all other clients to update their associated positions for the moved client.

Multiplayer Servers

While the client represents each player’s copy of the game, the server ensures that all the connected clients are playing the same copy of the game. Servers will often restrict what changes they accept from clients. For example, imagine we wrote a hack to change our money in a game. If it is a multiplayer game, the server will reject our changes. This is why single-player hacks will often not work in multiplayer.

We will discuss multiplayer fundamentals further in a future lesson.