Computer Components

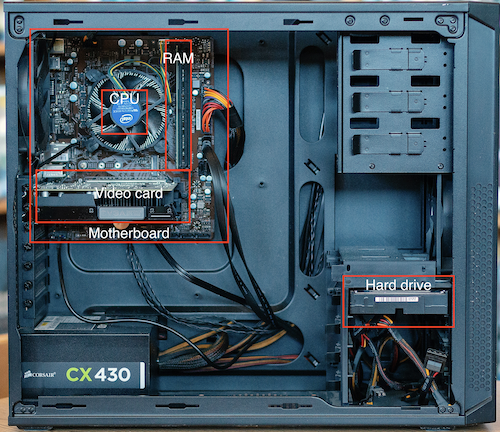

A typical computer has several connected components. Among the most important are:

- Hard-drive

- RAM

- Video card

- Motherboard

- CPU

If you were to remove the side of a desktop computer, the parts might be placed in a configuration like so:

For our purposes, we will only briefly address the first four components, and then we will focus on the CPU in the next section:

- Hard-drives are responsible for storing large files, such as photos, executables, or system files.

- RAM holds data that needs to be accessed quickly. Data is loaded into RAM from the hard-drive.

- Video cards are responsible for displaying graphics to the monitor.

- Motherboards tie all these components together and allow them to communicate.

The CPU

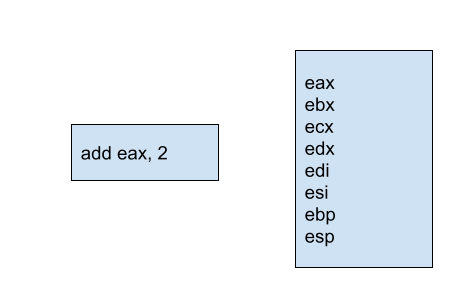

The CPU is the brain of the computer. It is responsible for executing instructions. These instructions are simplistic and vary depending on the architecture. For example, an instruction might add two numbers together. To speed up execution time, the CPU has several special areas where it can store and modify data. These are called registers.

Instructions

All computer programs are made up of a series of instructions. As we discussed above, an instruction is simplistic and typically only does one thing. For example, the following are some of the instructions found in most architectures:

- Add two numbers

- Subtract two numbers

- Compare two numbers

- Move a number into a section of memory (RAM)

- Go to another section of code

Computer programs are developed from these simple instructions combined together. For example, a simple calculator might look like:

mov eax, 5

mov ebx, 4

add eax, ebx

The first instruction (mov) moves the value of 5 into the register eax. The second moves the value of 4 into the register ebx. The add instruction then adds eax and ebx and places the result back into eax.

Computer Programs

Computer programs are collections of instructions. Programs are responsible for receiving a value (the input) and then producing a value (the output) based on the received value.

For example, one simple program could take a number as the input, increase the number by 1, and then move it into an output. It might look like:

mov eax, input

add eax, 1

mov output, eax

A more complex program would have many of these simple programs “inside” of it. In this context, these simple internal programs are called functions. Functions, just like programs, take an input and produce an output. For example, we could make our previous program a function that does the same thing. It might look like:

function add(input):

mov eax, input

add eax, 1

mov output, eax

We could also make another function that does a similar operation. For example, we could write a function to decrease a number by 1:

function subtract(input):

mov eax, input

sub eax, 1

mov output, eax

These two functions (add and subtract) can then be used to create a more complex program. This new program will take a number and either increment or decrement it. It will take two inputs:

- A number

- A mathematical operation, in this case, add (+) or subtract (-)

This new program will be longer and have two different ways it can execute. These will be explained after the code:

function add(input):

mov eax, input

add eax, 1

mov output, eax

function subtract(input):

mov eax, input

sub eax, 1

mov output, eax

cmp operation, '-'

je subtract_number

add(number)

exit

subtract_number:

subtract(number)

exit

This code has two functions at the top. Like we discussed, these take an input and then either add or subtract 1 from the input to produce the output. The cmp instruction compares two values. In this case, it is comparing the operation type received as input and a value coded into the program, -. If these values are equal, we go to (or jump to) another section of code (je = jump if equal).

If the operation is equal to -, we go to code that subtracts 1 from the number. Otherwise, we continue the program and add 1 to the number before exiting.

Comparing numbers and then jumping to different code depending on their value is known as branching. Branching is a key component of designing complex programs that can react to different input. For example, a game will often have a branch for each direction a player can move in.

Binary, Decimal, and Hexadecimal

Fundamentally, CPU’s are circuits. Circuits either have electricity flowing through them (on) or they do not (off). These two states can be represented by a binary (or base-2) numeral system. In a base-2 system, you have two possible values: 0 and 1. An example binary number is 1101.

We are familiar with a decimal (or base-10) numeral system, which has 10 possible values: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. An example decimal number is 126. This number can be represented in a more explicit format as:

\[(1 * 10^2) + (2 * 10^1) + (6 * 10^0)\]We can represent the binary number above (1101) in the same format. However, we will replace the 10’s with 2’s, as we are switching from a base-10 to base-2 system:

\[(1 * 2^3) + (1 * 2^2) + (0 * 2^1) + (1 * 2^0)\]Binary numbers can quickly become unwieldy when they need to represent larger values. For example, the binary representation for the decimal number 250 is 11111010.

To represent these larger binary numbers, hexadecimal (base-16) numbers are commonly used in computing. Hexadecimal numbers are usually prefixed with the identifier 0x and have sixteen possible values: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, and F. An example hexadecimal number is 0xA1D.

Programming Languages

Instructions are represented as numbers, like all other data on a computer. These numbers are known as operation codes, often shortened to opcodes. Opcodes vary by architecture. The CPU knows each opcode and what it needs to do when encountering each one. Opcodes are commonly represented in hexadecimal format. For example, if an Intel CPU encounters a 0xE9, it knows that it needs to execute a jmp (jump) instruction.

Early computers required programs to be written in opcodes. This is obviously hard to do, especially for more complex programs. Variants of an assembly language were then adopted, which allowed writing of instructions. They look similar to the examples we wrote above. Assembly language is easier to read than just opcodes, but it is still hard to develop complex programs in.

To improve the development experience, several higher-level languages were developed, such as FORTRAN, C, and C++. These languages are easy to read and introduced flow-control operations like if and else* conditionals. For example, the following is our increment/decrement program in C. In C, an int refers to an integer, or a whole number (-1, 0, 1, or 2 are examples).

int add(int input) {

return input + 1;

}

int subtract(int input) {

return input - 1;

}

if(operation == '-') {

subtract(number);

}

else {

add(number);

}

All these higher-level languages are compiled down to assembly. A traditional assembler then turns that assembly into opcodes that the CPU can understand.

Operating Systems

Writing programs to communicate with hardware is a time-consuming and difficult process. To execute our increment/decrement program, we would also have to write code to handle keystrokes from a keyboard, display graphics to the monitor, build out character sets so we could represent letters and numbers, and communicate with the RAM and the hard-drive. To make it easier to develop programs, operating systems were created. These contain code that already can handle these hardware functions. They also have several standard functions that are commonly used, such as copying data from one location to another.

The three main operating systems still in use today consist of Windows, Linux, and MacOS. All of these have different libraries and methods to communicate with the hardware. This is why programs written for Windows do not work on Linux.

Applications

Operating systems need a way to determine how to handle data when a user selects it. If the data is a photo, the operating system wants to bring up a specific application (like Paint) to view the photo. Likewise, if the data is an application itself, the operating system needs to pass it to the CPU to execute.

Each operating system handles executing uniquely. In Linux, a special executable permission is set on a normal file. In Windows, applications are formatted in a special way that Windows knows how to parse. This is referred to as the PE, or Portable Executable, format. The PE format has several sections, such as the .text section for holding program code, and the .data section for holding variables.

Games

With all of that out of the way, we can finally discuss games. Games are simply applications. On Windows, they are formatted in a PE format, identical to any other application. They contain a .text section that holds program code, made up of opcodes. These opcodes are then executed by the CPU, and the operating system displays the resulting graphics and handles input, like key presses.